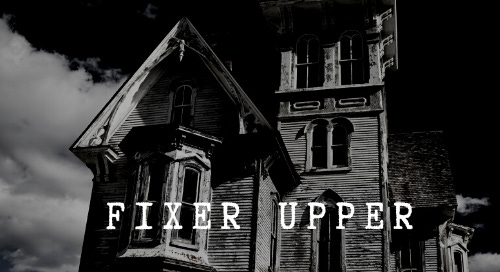

Is that house haunted, Grandpa? The belligerent crows watch the unnerved neighborhood kids scurry by every day on their way to school. Only the old-timers, and the swaying Sycamores, know for sure.

The glass panes are thin curtains glowing, creaking footsteps shuffle in the slanted attic, and a giggling toy chest groans open, just enough. A thick rope hangs from a rough hewn rafter, swaying, waiting for a master’s hands, perhaps a neck. A resting tricycle slowly rots. There are cots for sleeping on the sweeping porch on oppressive humid nights, a monolithic oak dresser standing sentry, its tongue out, a heaving mattress, and two reading lamps, languishing. A toothy-faced realtors sign gathering dust, spider webs are now for sale but not then…come on in folks…you’ll love the dining room… the stained glass…the light is terrific…plenty of room for the kids…let me show you the library…there’s a work shed out back…and a rose garden…And they sign here, sold, and they keep the pen.

Laughing, childish banter rises from two rooms downstairs, and in the kitchen, a radio croons. The teapot, a tempest boiling, is soon to blow.

The youngsters are at it again. One, the precocious one, a spitting image of Aunt Emma, her namesake, wobbles in shoes three times too big. The heels are stilts, and she dreams of make-up, a mink stole, and Ava Gardner, with Frank Sinatra on her arm. But, of course, she has no idea who Ava Gardner is. She watched her mother flip through Vogue, a gin and tonic sweating on the kitchen table, muttering…those shoes, my goodness…and Frank…Emma’s in pink lipstick and rouge, this little doll is preening in a mirror, lost in a tabloid reflection, play-acting, and the wallpaper smiles, the tiny white and yellow daisies bloom, and the sweet scent warms her nose. Emma’s brother, Lane, long gone now—too soon—is a cowboy today, herding cattle out back, drawing his six-gun. Lane was a fireman yesterday. Last week he was Audie Murphy, a broken broomstick, his rifle. Broomsticks die when the pressure is too great, a lantern is lit, and the man of the house comes from the moody cellar. His hands are soiled, his back grinding, as are his hips, and the boiler is on the fritz tonight, so a hot bath is out of the question.

He needs a hot bath, his joints demanding, his temperature rising. The house senses his mood and attends to its pipes, but it'll be too late. Tomorrow the Gazette will be delivered, and it will be a lump on the sidewalk, and an aware passerby or two will think…think…of pitching it on the porch…to be neighborly…but they don’t, won’t. Thinking is doing…, and they will skip the giving basket this Sunday and wonder if their pleas are heard. Just check the Dow Jones. That'll tell you who's winning, the man speaks to the stove, and her back, apron strings hanging, waiting for its master’s hands, eyes over the top of the newspaper, and he snaps it, folds it, licks his thumb, and gets on to the weather and the obituaries. He’ll end with the sports section, his reward for eating his daily ration of beets.

Standing now, he grabs a long-handled knife, a scimitar, used for breaking down hefty cuts of meat. He appreciates the curved balance in his hand. He studies those easy hips, and the apron strings swing, and in her ear, he breathes, and the red runs to her Raggedy Ann cheeks. Percolating and soft soap bubbles replicate, bloat, rise, and explode, and she wishes his hands weren’t so rough, now…Frank, the kids…and he halts. His name is Dan.

What are you doing with that knife? Her face loses its blush.

It needs sharpening, doll. He is a master at honing blades.

Soon it’ll be bedtime and good night lullabies. The statuesque grandfather clock attempts to erase time. Pages are turned back in the library; the books sense it; Dan heard what he heard, reading right to left, ending at the beginning.

You love me, Daddy?

You bet, sweetheart. Your brother, too.

And Mommy?

Say your prayers, Em.

If I should die before I wake…

The pilot lights flicker, and it's been years since gas fed the house. The copper pipes have been robbed; the hand-rubbed hardwood flooring plundered. Kitchen cabinets decide now if they open or close, and the whispering hangs in the worn-out air, the dust dancing, caught in moonlight piercing the cracked, stained glass. On still nights voices leak into the street and loiter on the porches of the neighbors, scratch at the screen, then dash…did you hear that…not sure; it could have been the radio…I don't know…shut the window…The piano, sold at auction before the windows became boards, still plays off key at sunrise to serenade the early risers, and the paperboy, an ace of spades clicking in his spokes. The cats scatter even as the mice tense, easy pickings under the sagging porch. The grass grows wild, and a street number, 247, is a faded outline on the chapped wood. A horseshoe remains nailed over the home’s front door, its luck long since vanished, vanquished.

For a once beautiful house, the defilement is savage and complete, yet it breathes.

Across the street at 248, a rocking chair pauses. That house ain’t haunted. It just needs a family and a wisp of smoke wails and rises from the resolute chimney. It could be a low-hanging cloud, though. That’s the Tucker’s old place. I’ll tell you about it when you’re older.